Future of 380 workers from the Canard plant still remains uncertain as some may be forced to relocate and/or seek different types of work, while others destined for the Berwick plant will join workers who have lacked a union contract since 2005. News commentary by TONY SEED and ENA BOUTILIER

HALIFAX (5 April 2007, updated 1 May 2007) – HERE is an old, familiar story: workers, farmers, their families and communities are being asked to bear the burden of the striving of a large food multinational to maximize its record profits, and the government leaps forward, not to sit idly by, but to consciously participate in the placating of that monopoly. As old is the story is, it takes new form far too frequently, as it is doing so once again in Nova Scotia in the winter and spring of 2007.

HALIFAX (5 April 2007, updated 1 May 2007) – HERE is an old, familiar story: workers, farmers, their families and communities are being asked to bear the burden of the striving of a large food multinational to maximize its record profits, and the government leaps forward, not to sit idly by, but to consciously participate in the placating of that monopoly. As old is the story is, it takes new form far too frequently, as it is doing so once again in Nova Scotia in the winter and spring of 2007.

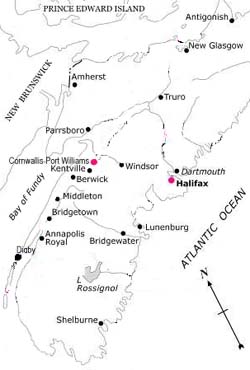

Maple Leaf Foods, part of the McCain family business empire, announced on 16 January that they would close a poultry processing plant in the rural village of Canard, in the Minas Basin of Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley, effectively laying off all 380 of the plant’s workers as of 27 April. The corporation claimed that the 50-year-old facility is too old to be run profitably, and that such a prospect would require the doubling of its current productive capacity. The shut-down is the latest in a series of closures of food processing plants in the Annapolis Valley.

The sudden move is devastating, affecting the right-to-be not only of the workers, but also of farmers and the community. The plant is said to have a payroll worth about $11 million and economic spinoffs worth about $40 million to the surrounding communities.

The decision by the Toronto-based monopoly also directly impacts on Valley farmers, as well as poultry producers in Prince Edward Island, both of whom are facing a vicious cost-price squeeze.

The Canard facility produces fresh poultry products, including branded and private label branded chicken, primarily for customers in Atlantic Canada. It processes approximately 250,000 locally-grown chickens each week, which came from about 20 poultry farmers. The closure of the Maple Leaf operation leaves rival ACA Co-operative as the only federally-inspected Nova Scotia processor. It has agreed to take 40,000 birds from a handful of farmers. Some 83 poultry farmers in the province produce about 43 million kilograms of chicken each year, according to the Chicken Farmers of Nova Scotia. Others are having to export to New Brunswick and Nadeau Poultry of St. Francois-de-Madawaska, owned by Maple Lodge Farms of Ontario – which means higher shipping costs. And its parent company is the third-largest chicken processing company in Canada.

Maple Leaf Foods is owned by Wallace McCain, formerly co-CEO of McCain Foods, along with the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. The corporation is also one of Canada’s largest agribusinesses, Canada’s largest pork and poultry processor – and also owns poultry and hog farms across the country. This multinational employs approximately 24,000 people at its operations across Canada and in the United States, Europe and Asia, and had sales of $6.1 billion in 2005. Its 2003 merger with rival Schnieders Foods gave it control of 80 per cent of the pork-packing industry in Canada.

Maple Leaf Foods is owned by Wallace McCain, formerly co-CEO of McCain Foods, along with the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. The corporation is also one of Canada’s largest agribusinesses, Canada’s largest pork and poultry processor – and also owns poultry and hog farms across the country. This multinational employs approximately 24,000 people at its operations across Canada and in the United States, Europe and Asia, and had sales of $6.1 billion in 2005. Its 2003 merger with rival Schnieders Foods gave it control of 80 per cent of the pork-packing industry in Canada.

In response to the announced closure of the Canard plant, the Nova Scotia Department of Education set up a “transition office” at the plant in what it said was an effort to explore career prospects and retraining possibilities for employees, as well as an effort to offer consultation on issues like employment insurance. The office was being set up in partnership with Maple Leaf Foods, the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, and Service Canada. As of press time, only 58 workers have found other jobs, and less than 60 per cent of workers had responded to the employment and training services being offered.

Middleton; rising unemployment in the Annapolis Valley

The closure of the Canard plan is, in various ways, merely the tip of the iceberg wreaking havoc in rural Nova Scotia. In the great fertile Annapolis Valley prosperity, like a guardian angel, is supposed to dwell. Here is great wealth in fat herds of cows, pigs and chickens, in fruit, vegetables and all manner of lesser farm produce. Truly a fat land and of course its inhabitants are well off; jolly, contented farmers. At least so say the newspapers, real estate sharks and retirement pamphlets issued by the counties courting well-off seniors to retire to the Valley. But stores are being boarded up and schools closed.

For the Annapolis Valley, the shutdown is part of a calamitous series of plant closures stretching back to 2003. Just the previous week, a decision by TRA Foods, owned by the Sobey’s family empire – “due to internal restructuring and job realignments” of their whole sale division – cost another 30 jobs due to Sobeys’ closing its administrative offices in the town of Middleton, also in the Annapolis Valley.

TRA Foods began operating in 1950 as a dry grocery products wholesaler in Middleton and was purchased by Sobeys Inc. in 1957. Sobeys is the second largest retail food distributor in Canada with annual sales of over $12 billion while employing 32,000 people. Since then, TRA has expanded into all of Atlantic Canada as a wing of the Sobeys’ empire. According to Canadian Grocer E-Newsletter (December 15, 2006), Sobeys’ parent Empire Company reported a profit rise in the 4th quarter of 2006, with earnings reaching $57.2 million, up from $48.6 million a year ago, with revenues reaching $3.31 billion (up 2 per cent).

TRA Foods began operating in 1950 as a dry grocery products wholesaler in Middleton and was purchased by Sobeys Inc. in 1957. Sobeys is the second largest retail food distributor in Canada with annual sales of over $12 billion while employing 32,000 people. Since then, TRA has expanded into all of Atlantic Canada as a wing of the Sobeys’ empire. According to Canadian Grocer E-Newsletter (December 15, 2006), Sobeys’ parent Empire Company reported a profit rise in the 4th quarter of 2006, with earnings reaching $57.2 million, up from $48.6 million a year ago, with revenues reaching $3.31 billion (up 2 per cent).

Port Williams

In 2004 the closure of the last vegetable canning operation in Atlantic Canada, Avon Foods in the nearby village of Port Williams, not only affected workers but also producers who lost a large share of their income.

In 2004 the closure of the last vegetable canning operation in Atlantic Canada, Avon Foods in the nearby village of Port Williams, not only affected workers but also producers who lost a large share of their income.

With the closure of the Britex textile plant at Centrelea near Bridgetown in October, 2003 with just over $4.4 million in unpaid loans to the provincial government, and Maple Leaf’s Shur-Gain livestock feed mill in Port Williams (and in Sussex, NB and in PEI) in 2005, the resulting layoffs put over 200 people out of work. According to Statistics Canada, Annapolis Valley employment is up just slightly from January, 2006 but the unemployment rate is down substantially from 9 per cent. Six per cent is the lowest January unemployment rate recorded for the Annapolis Valley for at least the last 20 years but this figure is a mirage. This is because the Valley’s labour force is smaller this year by almost 2,000 people, a figure that does not include the 380 workers to be laid off this April at Canard by Maple Leaf Foods.

Maple Leaf (Larsen’s) in Berwick

Meanwhile, 400 workers employed by a Maple Leaf-owned pork processing plant (Larsen’s) in the town of Berwick (pictured), further south in the Annapolis Valley – represented by the Atlantic Meatpackers’ Union (AMU) – voted on 17 January, the day after the Canard announcement, to reject a contract that was offered by the company. Larsen’s workers had been without a contract since September 2005, a 16-month period.

Meanwhile, 400 workers employed by a Maple Leaf-owned pork processing plant (Larsen’s) in the town of Berwick (pictured), further south in the Annapolis Valley – represented by the Atlantic Meatpackers’ Union (AMU) – voted on 17 January, the day after the Canard announcement, to reject a contract that was offered by the company. Larsen’s workers had been without a contract since September 2005, a 16-month period.

Widespread speculation is also being generated about this plant’s future. News of difficulties for workers in both Canard and Berwick come as Maple Leaf is now aiming to consolidate its meat processing operations throughout the country in Brandon, Manitoba after having decided in October, 2006 to exit the pork export industry. And much of the Larsen’s plant production is geared for export.

Larsen’s takes 80 to 85 per cent of Nova Scotia’s pork production from hog producers.

Despite the pressure on the workers, Ted Jones of the AMU said, “We weren’t scared – we’ve heard the rumours every time we’ve been through a contract, and we’re tired of them. We’ve been through wage freezes, rollbacks – we deserve it for all we’ve done to help the company get through things.”

Maple Leaf offered a 25 cent hourly increase in September of both 2007 and 2008, but did not live up to union demands in terms of pension and sick benefits, retroactive money and signing bonuses. Many workers are leery of the long-term future of the Berwick plant. Superficially, there are no apparent plans to close the facility as in the case of Canard. In fact, plant manager Mike Larsen publicly stated he will consider hiring former Canard workers in the Berwick plant, a statement made shortly before news broke of the creation of the Canard facility’s transition office on January 24. Nevertheless, he acknowledged “quite a migration of Larsen’s workers” has taken place. The AMU’s Jones adds: “We’ve lost 100 people in there the last year,” citing the lure of Western Canadian jobs and regional insecurity as enough incentive to attract even settled families. “It’s hard to get people.”

The tombstone of rural Nova Scotia

The rationale of Maple Leaf’s current “restructuring” efforts is strongly reminiscent of actions taken by other key monopolies in the food processing industry. In 2005, for instance, Québec pork and poultry producer Olymel, a division of Qu?bec’s huge La Co-op fédérée and a rival to Maple Leaf Foods, threatened to consolidate operations in St. Bonifice, Manitoba (in a joint plant with Saskatchewan-based Big Sky Farms and Manitoba’s Hytek). It declared it wanted to close several facilities in Québec on the grounds that it needed to modernize its production units in the interest of being both nationally and globally competitive. Recently, on 13 February 2007, it forced Olymel workers in Vallee-Jonction, Quebec, to vote to accept massive wage cuts in order to return to work under the spectre of the threat of closure.

In the case of workers from the Canard plant in Nova Scotia, their future remains uncertain. Some may be forced to relocate and/or seek different types of work or go down the road, while others destined for the Larsen’s plant in Berwick will join the other workers who have lacked a union contract since 2005. The burden of the crisis is put on the backs of these workers, the poultry and hog farmers, the main street business people and their communities, and their very right to be, leaving ruin in our rural communities.

Even if they are lucky enough to remain employed, workers are being shuffled from one location to another without regard to the costs of transportation and relocation, while small rural communities such as Canard and Port Williams suffer a decimation of a significant part of its economic base – all under the watchful eyes of our elected officials, working hand in hand with one of the region’s richest business families. In the same way, the monopolies shift meat and feed grain supply from region to region and country to country and strategically locate their operations to maximize profits and externalize costs, regardless of the consequences to either the farmers, the region or the nation. Meanwhile, they blame the wages of the worker and the prices of the farmer or the catch-all euphemism of “rising energy costs” for rising food costs to the consumer.

The vertical integration of the food industry means that a handful of huge packers, through their direct and indirect control of corporate industrial farms, and the elimination of the “single desk” selling system, dictate monopoly prices through contracts with large beef and hog producers, eliminating the market power of the small- and medium-sized family farm producers. Through exclusive contracts with the supermarket chains – Sobeys, Atlantic superstores and Wal-Mart, etc. – this cartel is squeezing all non-monopoly competition, from independent meat-packing facilities to independent retail chains such as the co-ops. “Similarly, organic agriculture must be destroyed,” notes the Union Farmer Monthly to cut off the escape route from the factory-style farm.” They provide “forms of resistance, and they provide a working counter-model.”

At the same time, the consumer who tries to respond to the niche marketing programs to “buy local” is blocked by generic private-label or unbranded goods, such as Sobeys “Our Compliments” and Atlantic Wholesale’s “President’s Choice”, which make it impossible to discern where and from whom the product originates.

Protection of the local marketplace and the local market infrastructure to facilitate direct links between the farmer and the consumer is important, but the “buy local” program seems to have another role: to suggest that the source of the problem lies with the tastes of the consumer, that the problem is primarily one of consumption, and that the solution lies in appeals to the non-existence conscience of the supermarket chains. It depoliticizes the consumer from taking a stand with farmers and labour. Of course, Sobeys et al do “buy local”, mostly perishables, cheaply positioned behind the major display and prime shelf space paid for by the large food monopolies.

This is symptomatic of a larger national political problem. All political decision-making is in the hands of relatively few people – all of whom accept without question the dominant paradigm of global competitiveness as a goal to be pursued at all costs. Parties in power federally, in Alberta, and elsewhere, most notably in the US, are waging an extensive campaign to turn over all aspects of food production and distribution to these transnationals such as Maple Leaf Foods, Cargill and Tyson. In the name of “competitiveness”, “efficiency”, “free market” and “food security” agencies such as the Fraser Institute, the Calgary School, the Frontier Centre, and the Atlantic Institute of Market Studies are campaigning to eliminate equalization payments and price support to small farmers. The defence of private wealth and its future expansion is the basic consideration of these parties and “think tanks.” The monopolies lay off workers and block their unionization, wipe out farmers, and devastate communities and entire regions because they can.

What official political leadership in this province or the nation has had the courage to uphold its responsibilities towards the society, to defend the public good and stop the attacks of the monopolies? You want the supercentres open on Sunday? There’s no problem: Corporate Research uses polling to prove the case; the media, lusting for Sunday advertising, campaign for consumer secularism; the police tolerate violations of bylaws by the supercentres; and the big tourist interests justify it as a means of attracting cruise ships. In the name of global competitiveness, the workers in Berwick – as at Vallee-Jonction, Québec, or in the forest sector and their communities, such as what transpired with Stora Enso in Port Hawkesbury last year – are being intimidated with the long-term possibility of closure into accepting working conditions that they would not accept in any other circumstance. The fruits of the earth, the rights and existence of workers, the small to medium-sized holdings of the farmers, their communities and even the factories and mills owned by big capital are considered dispensable within the fundamental aim to defend and expand monopolies and their empires. The sole solutions being proffered are to go down the road or the canard of buying fresh food and farm products locally.

Self-sufficiency in food is an important element of national sovereignty. The cases of Canard and Berwick are a graphic illustration of the need for new political leadership – a leadership that stops paying the rich, develops a national economy including regionally-self reliant agriculture and food, upholds social responsibility, invests in social programmes – and new political mechanisms that make such governance possible.

Only then can this old, familiar story truly become an artifact of the past.

Originally published on Shunpiking Online, May/June 2007

Source: http://www.shunpiking.com/ol0404/0404-AC-TSEB-maple4ever.htm